Most people don’t remember the first time they worked in the evening, and even fewer people know when the last evening work session is going to be.

The one thing we do know is that this shift never seems to happen abruptly. It’s often gradual — a few more Slack messages after dinner, a dashboard that stays active past 9 PM, or a team member who says they prefer to “catch up later.”

In doses, none of these examples seem like glaring red flags. For asynchronous teams, it may even look like scheduling flexibility is working as intended.

But is it really?

When late hours become consistent (and especially when they stack on top of already full days), they start to signal something else. In this piece, we’ll take a look at:

- What 2026 data reveals about triple-peak days

- Why evening work can be either healthy or harmful

- How broken core hours are often the hidden driver behind overload

Let’s begin.

Stay in the loop

Subscribe to our blog for the latest remote work insights and productivity tips.

The quiet growth of evening work

Evening work doesn’t usually begin as a policy. Oftentimes, it begins as an innocent preference that might appear in the form of:

- Blocking off one’s morning for school drop-off and finishing later.

- Logging back in after dinner because that’s when their calendars are finally meeting-free.

- A time zone needs overlap issue that leads to a call being pushed back an hour later than usual.

At first glance, this looks like healthy asynchronous work, but the problem is that evening work rarely replaces daytime work. More often, it attaches itself to it.

The meetings stay, the messages continue, the expectations don’t shrink. So the workday stretches. From the outside, it can look like commitment. Or autonomy. Or “hustle.”

But when employees working late becomes a pattern instead of an exception, it’s often an early signal. Not that they perform badly or they’re lazy, but that something is fundamentally misaligned in how the day is structured.

Working at night is rarely the root issue. More often than not, it’s the overflow of work due to unnecessary meetings that causes it.

What 2026 data shows

For the AI Productivity Shift report, we analyzed anonymized data from more than 140,000 workers across 17,000 organizations.

These aren’t survey responses about how people feel their days are going, but behavioral data — how time is actually spent across meetings, focus blocks, apps, and after-hours work.

According to the 2026 Global Trends and Benchmarks Report, the average person logs about 2 to 3 hours of real focus time per day. That’s uninterrupted time inside the tools that actually move work forward.

The rest of the day? It’s consumed by meetings, messaging, coordination, and switching between apps. Inside that backdrop, something interesting shows up.

Roughly one in five weekdays follows what we call a triple-peak pattern. In simple terms, that means three noticeable surges of focused activity: one in the morning, one after lunch, and a third in the evening.

These days are not the norm, but they’re not rare enough to ignore either.

A triple-peak day is almost like compressing two workdays into one. On paper, it can look productive:

- Total hours stretch significantly.

- Focus percentage may tick up slightly.

- Fewer meetings and interruptions.

But how the day is shaped tells a deeper story.

People don’t add a third work block at night because they’re bored. They add it because the middle of the day often can’t support sustained focus. The evening becomes reclaimed time.

The takeaway is simple: triple-peak days are real, measurable, and powerful if deliberate. But when they become routine, they’re often a signal that something in the core of the workday needs to change.

If you want to learn more, the full report goes deeper into how this pattern varies by role, workstyle, and time zone overlap.

When evening work is healthy, and when it’s a red flag

Evening work isn’t automatically a problem. Some people think better at night, and if there’s anything remote work has taught us, it’s that some lives simply don’t fit inside a clean 9-to-5 block.

All of that’s okay, but the real question isn’t whether work happens after dinner. The question is why it’s happening.

There’s a version of evening work that reflects autonomy, but there’s another that’s problematic.

When it’s healthy, it tends to look like this:

- Clear core hours. Everyone knows when real-time collaboration is expected and when it isn’t.

- Protected focus time during the day. The middle of the workday isn’t sliced into fragments by constant meetings.

- Substitution, not addition. Evening work replaces a block of daytime hours; it doesn’t stack on top of them.

- Explicit permission to disconnect. Logging in later doesn’t mean staying available all day.

In that version, the third peak is intentional. Someone leaves at 3 PM for school pickup, a workout, or simply a break. They return later for a stretch of deep work.

The red-flag version feels different.

It shows up when the day is already full, and the evening becomes recovery time for work that couldn’t happen between meetings. It shows up when being “flexible” turns into being reachable at all hours.

When evening work signals a system issue, it often includes:

- Meetings spread across the entire day. No clean blocks for sustained work.

- Catch-up work at night. The real progress starts only after the calendar empties.

- Always-on expectations across time zones. Someone is always overlapping with someone else.

- Unclear boundaries. Core hours exist on paper but not in practice.

That’s when evening work stops being a personal preference and starts becoming a structural workaround. What’s worse is that structural workarounds have a way of becoming culture.

The hidden driver: Broken core hours

Most teams don’t lose focus because individuals lack discipline. If that were the case, no business would be profitable.

Instead, they lose it because the day is cut into pieces.

A standup at 9:30, a check-in at 11, and a quick sync after lunch. None of these meetings are outrageous on their own. In fact, each one probably has a reasonable purpose.

The problem is the spacing. When meetings are scattered across the entire day, they don’t just consume the time they occupy — they also interrupt the time around them, leading to context switching that kills whatever momentum team members had before hopping on Zoom.

Real focus needs a runway: a long enough stretch that your brain can settle into the work and gain momentum. A fragmented calendar erases that runaway, forcing people to adapt the only way they can.

They may answer messages in between, push deep work later, or tell themselves they’ll “finish tonight.”

This is where evening work starts to make sense.

If the middle of the day can’t support uninterrupted work, the edges of the day absorb it. The evening becomes the only quiet block left. Over time, that workaround turns into routine.

This is why core hours have to be a design decision.

Core hours are simply the agreed window for real-time collaboration. They create a shared overlap so decisions can happen, but they also create protected space outside that window. Without clear core hours, Parkinson’s law kicks in. But with them, the day has shape.

Why leaders miss the signal

Most leaders aren’t ignoring evening work on purpose. They’re looking at other things (or not online altogether), like revenue, delivery timelines, and client satisfaction, among many other metrics.

If the numbers that traditionally signal “performance” are steady, a few late-night hours don’t automatically stand out. In some cases, they even register as a positive, as the team looks engaged and willing to go the extra mile.

Evening work can easily be interpreted as commitment, flexibility, or autonomy in action (adults can manage their own time, after all).

The problem is that most organizations weren’t built to track focus time, fragmentation, or after-hours creep as first-order metrics. They’ve spent years measuring output, not the conditions that make output sustainable. So when capacity starts to strain, it doesn’t immediately show up in the dashboard.

It might appear as overfilled calendars, roles that have expanded without anyone’s knowledge, or tech stacks with constant new additions.

By the time it surfaces as burnout or attrition, it looks sudden.

But evening work is rarely sudden; it’s just subtle. If leaders aren’t explicitly looking at how the workday is structured (not just what gets produced), they can miss it completely.

What high-performing teams do differently

The teams that avoid this drift don’t rely on individual discipline. They don’t ask people to “manage their time better” or squeeze more efficiency out of an already brutal day.

Instead, they adjust the structure around the work. They assume that if evening work keeps showing up, something in the system needs attention.

If you’re unsure if your team is burning out or thriving under triple peak conditions, here are a few patterns that tend to separate high-performing teams from the rest:

- They treat focus time as a real metric. They look at how many hours people actually have for uninterrupted work and notice when that number drops.

- They define when real-time work happens. There’s a clear window for standups, decisions, and cross-team calls. Outside of it, the default shifts to async. Meetings don’t bleed into every hour of the day.

- They make evening work explicitly optional. If someone chooses a third peak, it’s a trade-off, not a requirement.

- They use hours and after-hours activity as early warning signals. When 50-hour weeks or consistent late-night activity show up, it triggers a conversation about scope, staffing, or the definition of roles.

High-performing teams don’t eliminate flexibility because they know how potent it is. They do give it guardrails by designing the day in a way that allows for progress to happen inside it, not after it.

Thriving or surviving: The right tools for healthy evening work

Evening work isn’t the enemy. The truth is, it can be incredibly promising when used right. But when it becomes routine, it’s usually telling you something about how your days are structured.

You can’t fix that by asking people to try harder, because it isn’t fair to ask them to. You fix it by redesigning the rhythm by:

- Clarifying core hours

- Preventing unnecessary meetings

- Protecting focus time

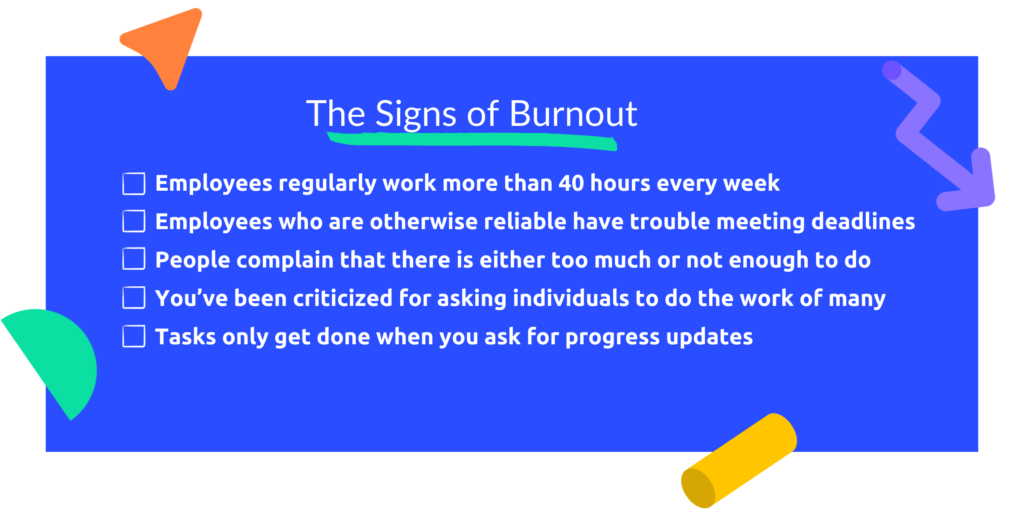

- Spotting signs of burnout

Our 2026 Global Benchmark Report goes deeper into the benchmarks behind these patterns: what healthy focus time looks like by role, how time zone overlaps can be structured more fairly, and where guardrails on hours actually make a difference.

Most popular

How Much Deep Work Do Employees Really Get?

Employees are more distracted than you think — and it isn’t due to lack of discipline. In fact, the blame falls far from them:...

What AI Time Tracking Data Reveals About Productivity in Global Teams (2026)

Global teams face one problem, and it isn’t total hours worked. Measuring time spent in meaningful, focused work can be a challe...

How AI Is Transforming Workforce Analytics: A Roadmap for Team Leaders

Why do you think most leaders struggle with managing their teams? While many believe it’s a lack of data, AI workforce analytics...

How AI Is Transforming Performance Management

Performance management has always lived in an uncomfortable space. It asks managers to measure things that are often hard to see �...