When trying to grow and sustain a business, two operational pressures often come to a head as companies plan to achieve future growth: productivity vs wages.

Especially with today’s globalization, companies have chosen to pursue productivity, often to the detriment of all else. However, achieving that aim requires a team, and their gains ultimately lead to increased productivity.

So how should a business compensate them today to ensure that team members stay and perform well in the future?

The workplace faces a structural and often fundamental challenge. What should it pay employees so that they improve the business, and what should it reinvest in the business for that same productivity gain?

This dynamic not only influences the health of economies but also shapes the daily lives of team members and the strategies of businesses worldwide. Understanding this relationship is not just an academic pursuit; it is necessary for anyone looking to navigate the modern workplace effectively.

And like many things in our current markets, it comes with a gap that often defines the conversation. Tackling pay and productivity growth comes with an understanding of labor productivity and median wages and the pay gap between these two when one side of that equation grows.

Boost your team’s efficiency with Hubstaff's productivity tools

So, what is this productivity-pay gap?

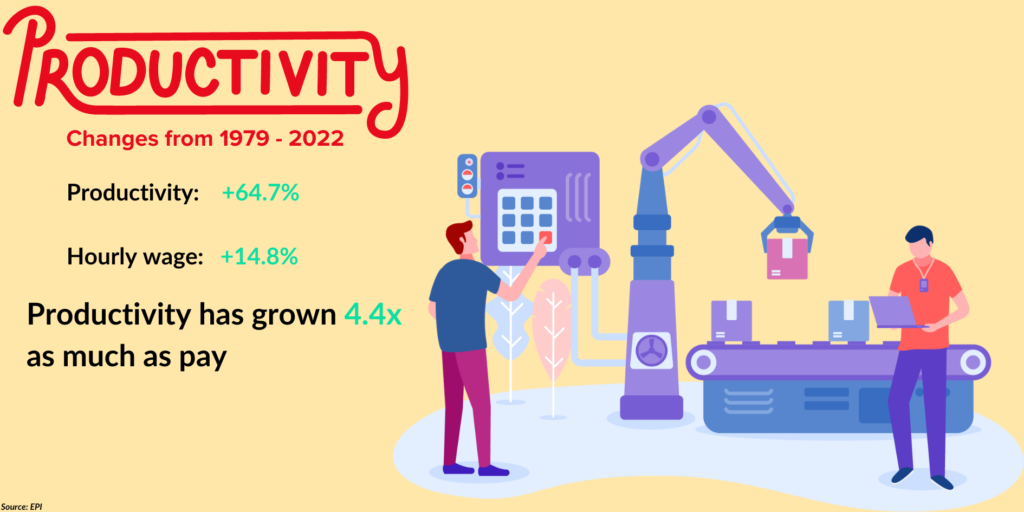

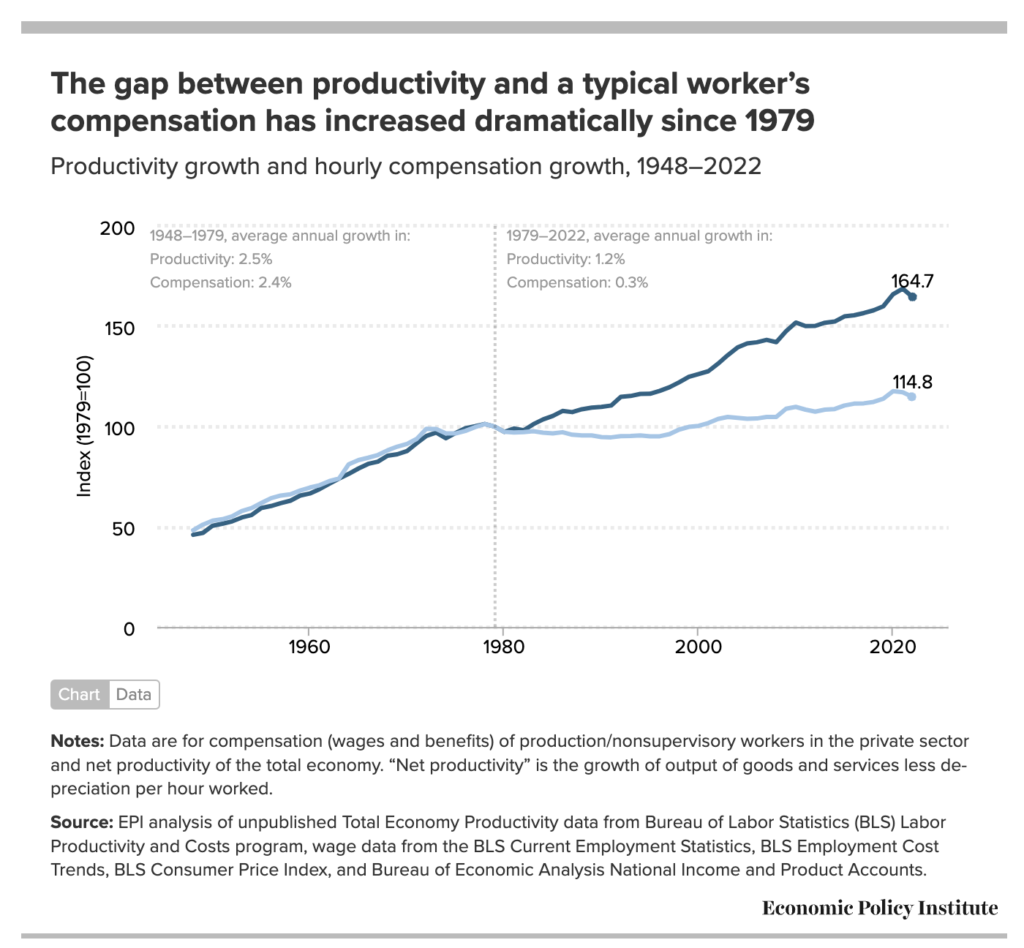

The “productivity pay gap” refers to the stark divergence between the rate at which worker productivity increases and the rate at which wages grow. It demonstrates that productivity has massively outgrown wages, leaving your typical worker far behind.

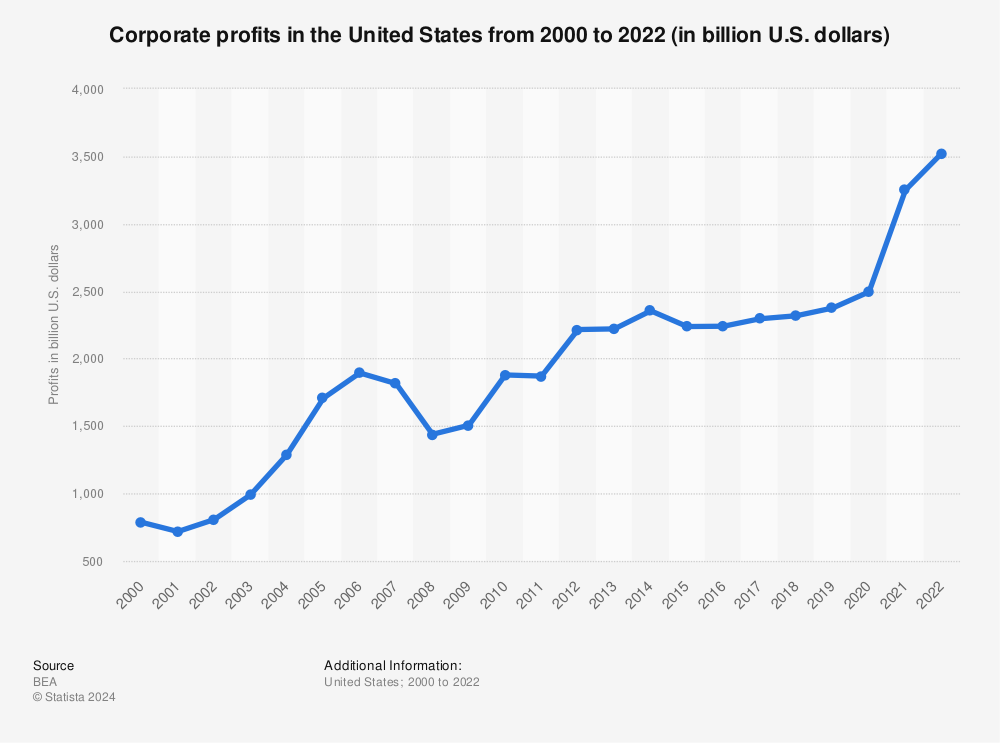

Not surprisingly, corporate profits tend to scale with or faster than productivity, so companies are directly reaping the benefits of the productivity gap.

From an economic standpoint, productivity measures the output of goods and services. It’s often measured per labor hour or hour worked. When comparing productivity over time, we look at net productivity — the growth of that output of goods and services, subtracting any depreciation per hour worked.

The modern fiction has long been that as team members become more productive, their wages rise correspondingly. However, that has not been true for many of today’s workers.

This shows us that the pay gap here is between workers at different tiers within an organization. This may have factors similar to other wage gaps, such as gender or education. However, wage inequality for these labor statistics focuses on income inequality among typical workers, assuming that other characteristics are evenly distributed.

Crucial to this discussion is the realization that it has not always been this way. We do not need a productivity-wage gap to progress.

A brief historical perspective

The post-World War II era saw a close alignment between productivity and wage growth, particularly in economies like the United States. However, from the 1970s onwards, this alignment began to diverge.

Industrialization, the rise of modern factories, and jobs moving away from farming activities all contributed to the increase in productivity. Wages kept up, for the most part, and prices in the economy were relatively stable. Starting in the 1960s, these factors became less consistent.

Scholars in the 1970s studied this trend, finding that worker pay in the late 1960s only rose about half as quickly as in the ‘40s, ‘50s, and early ‘60s. Despite continuous improvements in worker productivity, wages have stagnated when adjusted for inflation. This disparity has fueled debates around economic policy, labor rights, and the equitable distribution of wealth.

Reason for the change in hourly compensation growth

Some of the potential reasons cited for the change in hourly compensation growth include:

- Labor shortages due to world wars and regional conflicts

- The globalization of labor and economies with new pressures, such as the 1973 oil embargo and ongoing price manipulation

- Inflation became a serious national issue for many large countries, starting in 1966

- Shifts in social programs, both creating and dismantling safety nets and worker protections

- Declines in bargaining power and union activities

- Decline in the spending power of some global currencies

Inflation plays a significant role in the shift in the value of wages. It also impacts why pay raises in the modern context don’t feel as valuable, even if they were to reach the same percentages as rises in the 1950s and 60s.

The price stability that much of the world had after WWII ended in the 1960s — US economics often peg the year 1966 when looking at our economy. Postwar recessions, consumer goods increasing dramatically in price, and sustained high levels of inflation all harmed productivity vs wages for growth.

In these prior decades, most workers could meet higher living standards off of a single income. Labor statistics show the productivity pay gap and rising inequality are hallmarks of capital depreciation and market responses. It is not always a direct effort of wage suppression, but the declines have similarities to note.

Productivity, wages, and profit

The relationship between wages, productivity, and profit is a classic economic puzzle. From a business perspective, the goal often involves maximizing profit, which can be achieved by increasing productivity while controlling wage costs.

However, this approach can lead to a widening pay gap and, potentially, wage inequality. When companies pursue this across all staff, they tend to suffer for final products and overall profitability, followed by revenue declines.

So, many companies rely on economic theories that suggest that a balance is necessary for sustainable growth. According to these theories, some team members should be fairly compensated as productivity increases. That ensures reliable growth for companies to move through a positive cycle of investment, scaling, and productivity gains.

Other wages can be allowed to stagnate to protect against concerns due to natural changes in skill requirements, attrition, and other factors businesses plan for.

The issue that many workers today have is that these policies and theories are not transparent when companies apply them. Team members often feel left out of the group given reliable wage increases. Managerial roles and executives typically see the most substantial gains.

Lower-rung employees are shown these roles as potential growth options for their future. However, companies rarely have these kinds of opportunities for every team member. So, employees see their wages stagnate while the promise of growth remains purposefully elusive.

Look at the margins

In a pure economic theory, wages should be based on the marginal product of labor. That’s the amount of revenue generated by the added output from the last worker hired.

Take it from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

The goal is to set wages based on how much the individual produces for the company. In practice, that has not been the case when looking across an economy, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Instead, the Bureau of Labor Statistics notes that various external pressures prevent this correlation in growth because the reality is that not all else in a company’s revenue equation is equal or stable. Productivity increases allow for more goods and services to be produced using the same amount of labor, but companies can’t escape these external pressures.

It and other economic analyses ask people to look at margins to understand what might be feasible for wage and productivity growth. One core reason is that margins show real-world capabilities when accounting for inflation, one of the most disruptive forces in productivity vs wages.

If we could live in economic theory and not the reality of the market:

- Productivity increases would increase output and revenue per labor hour

- Real wages would increase correspondingly

- With the increase immediately captured, inflation should not rise as a result

However, in current markets, productivity gains are often used to help companies maintain or grow revenue without increasing prices. But what if inflation or other outside forces increase and companies are already suppressing pricing via productivity?

To maintain low costs, they now need to control wages.

If real wage growth were to rise past this point — employee productivity increase minus the price controls — workers could be paid more than the value of their output. That could force companies to increase pricing.

When the desire to maintain low pricing is strong, compounded by the need to keep positive and growing margins, companies will deflate wages relative to productivity in nearly all cases.

Impact of decline in workers’ share

The Economic Policy Institute points out one essential concern around productivity vs wages: companies can benefit (in the short term) by stagnating one side of the equation.

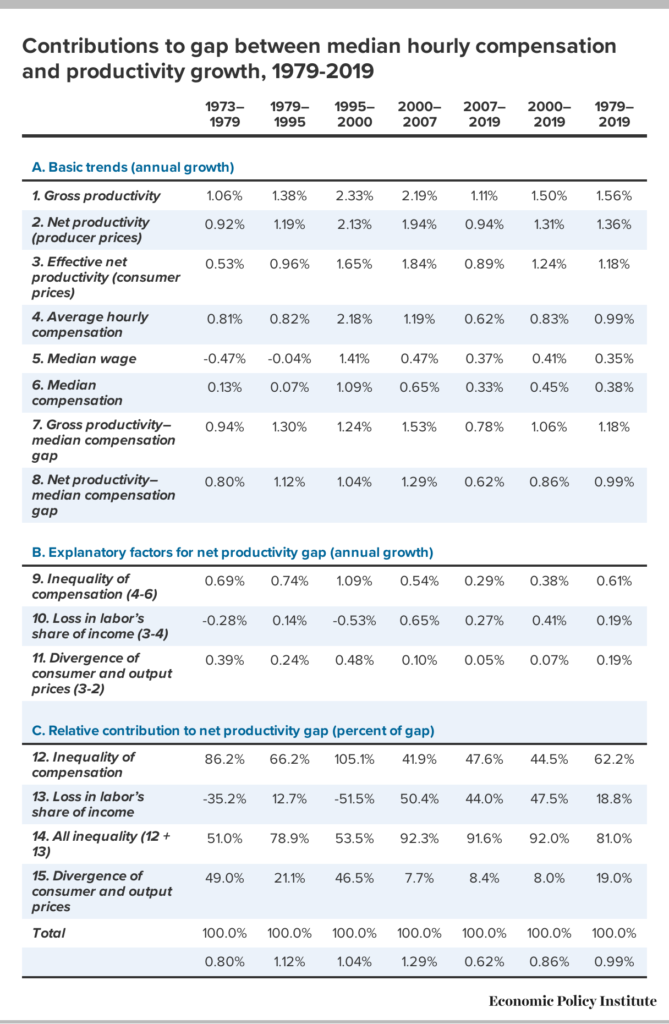

From 1979 to 2019, net productivity grew 1.36% annually, while compensation grew 0.38% annually. When its economists reviewed this stark difference, they found the two biggest things driving the productivity-wage gap were the decline in labor’s share and a growing inequality in compensation.

Inequality is the disparity in baseline pay and pay rate increases among workers. It is prominent in roughly the top 10% of workers across industries. However, comparing the median to the top 1% of those compensated — typically restricted to executives — shows a substantially higher inequality.

The other term, labor’s share of income, is the share of company revenue going to workers as opposed to other factors of production, such as capital.

Its analysis shows the combination of these two factors “explains 81.0% of the growth of the productivity–median hourly compensation gap.” Inequality in compensation growth has become worse in recent years.

When looking at productivity gains relative to these employee losses, the EPI analysis says the productivity-wage gap costs the median worker roughly $9 per hour.

For the policy side of the conversation, the analysis points to some concerns that may worsen the gap and further drive down wages relative to spending power and inflation:

- Government policies that remove worker rights

- Legal cases removing worker protections and consumer protections

- Policy decisions that shift tax burdens from companies and wealthy individuals to median individuals

- Weakening labor unions and increased anti-union activities that go unpunished

- Failing to achieve full employment

- Cycles of layoffs when companies enjoy increasing profitability

- Corporate globalization

- Restrictive employment contracts, such as non-compete agreements

- Outsourcing for wage and profit redistribution

The relationship between minimum wage and productivity

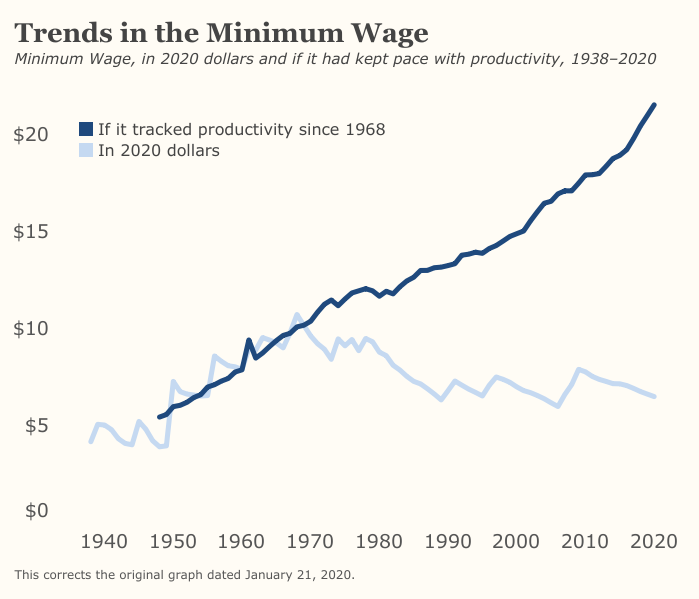

According to The Center for Economic and Policy Research, if the minimum wage had kept up with productivity growth since 1968, it would have reached $21.50 in 2020. It could be close to $25 now.

That can be upsetting to see as a worker because we know that minimum wage has not kept up with inflation while profits have kept up. The companies charging us more for goods are paying what feels like less.

For example, prices for consumers in 2023 rose 3.4% while costs for companies to make goods increased only 1%. Even as costs to produce goods decline from pandemic highs, consumer costs are still rising.

That reality impacts those who make minimum wage the most. This situation makes the debate over the minimum wage and its impact on productivity contentious.

Proponents of higher minimum wages argue they can increase worker productivity by attracting better talent, reducing turnover, and improving morale. Critics contend that a minimum wage that is too high might lead to job losses as businesses automate roles or hire fewer workers to control costs.

Research and historical studies

Historical studies show that the link between minimum wage and productivity exists but is conditional. Increasing the minimum wage has a “robust positive effect on the productivity of low types and no effect on high types.”

Kellogg Institute researchers worked with a company to study the impact of higher wages on individual productivity. They studied 10,000 salespeople at more than 200 stores from that single company who received a slight raise to the minimum wage the company paid.

They found that increasing wages increases productivity, though the extent of the increase depends on roles and locations. However, they did note that the higher salary at least partially pays for itself.

According to the study, increasing workers’ minimum wage led the company to sell 4.5% more goods across all workers, even if the number of customers remained constant.

The study found:

- Increased wages created a better employee experience

- Sales teams increased effort, connecting the sales to the wage

- Sales increased even when a physical location had no increase in customer volume

- Higher wages led to 19% fewer firings for cause

- $1 increase in minimum wage could lead to a profit decrease in the short term

One crucial piece in the Kellogg study was that the increase in the minimum wage for employees had a positive impact only in stores with more supervisors to monitor employees. That means people need to be held accountable for their work.

Increasing wages without increasing accountability can lead to decreased productivity because there’s no incentive to perform well for the reward.

The Seattle Example

The federal minimum wage in the US has stagnated for years. Seattle aimed to address that with a policy that raised its minimum wage to $15 in 2015. This experiment has since generated significant study and review.

A few key takeaways from the effort include:

- The take-home pay of people already at low wages saw significant increases

- At the same time, employers reduced hours for low-wage jobs

- Hiring slowed down, but those already employed had wage gains

- Companies have increased service fees and product costs to compensate for increased wages

- Reports vary by industry, but overall, both productivity and profits seem to have increased

Nominal wage vs. real wage

Understanding the difference between nominal and real wages is crucial in this context. Nominal wages refer to the face value of earnings, whereas real wages account for purchasing power, adjusted for inflation. Even if nominal wages increase, if the cost of living rises faster (as measured by the consumer price index, for example), real wages may stagnate or decline, affecting overall productivity and economic well-being.

Real wage encompasses how much you’re paid and how much that feels like you have to spend in your city. It can play a substantial role in job satisfaction and employee engagement. Some economic models may call this real compensation instead, but the term has no meaningful difference among the studies we reviewed.

Productivity plays a crucial role in real wages. According to this study review from Brookings, a 2% productivity growth can generate a 4% increase in real wage growth.

Many reading this may not have felt this in recent times of that productivity growth because the pandemic came with various price shocks at every point of a product, from raw materials through shipping and final purchases online or from shelves.

If the pandemic pricing ever recedes — such as the shrinkflation — the research says there is a chance that recent productivity gains would lead to real wage increases.

Wage growth vs productivity increase

Time and again, research shows us that wage growth positively impacts productivity. Internal and customer-facing workers respond positively to wages by reducing turnover and increasing on-the-job productivity.

Nuances depend on the people, the work, and the local culture. Much of this can be hard to separate, such as areas where women respond more highly to wage increases. And there are times when productivity gains are linked to decreased turnover instead of a specific dollar value wage increase.

Workers in the European Union will have the same linkages but changes to wages and other facets may yield different effects. That’s because a 1% increase in productivity created a 0.4% to 0.7% increase in compensation for the average non-supervisor.

The EU Commission notes that productivity and wages are tied together. However, it says that declining compensation and reduced company growth have not resulted in decreased productivity.

Productivity alone may not be a reason to increase wages from a business perspective.

The reaction of the EU to this news may take some in the US by surprise. The body calls for governments to pursue full employment, look for ways to increase living standards and reduce inequality, and direct reviews for redistribution in cases where profits and the productivity-wage gap rise unchecked.

Globally, the trends in wage growth versus productivity increase paint a complex picture. While some regions have seen both metrics grow hand in hand, others have witnessed a significant lag in wage growth despite productivity improvements. This discrepancy raises questions about the distribution of economic growth and the factors influencing wage-setting mechanisms.

It may not be a problem we can tackle on a global scale.

Current trends and future outlook

The future of the productivity-wage relationship is uncertain, influenced by technological advancements, globalization, and policy decisions. Current trends suggest that the productivity pay gap may continue to widen without intervention, exacerbating economic inequality.

However, there is also a growing recognition of the need to address this gap, with discussions around policies that foster a more equitable distribution of productivity gains. The Bureau of Labor Statistics data on private sector workers and average compensation growth may help improve economic development.

However, it is often difficult for a company to measure productivity, hourly wages, and pay growth to create a plan for appropriate total compensation. Enter Hubstaff.

The Kellogg research highlighted the need to hold people responsible and have some monitoring in place. Hubstaff makes that possible for remote, asynchronous teams. We help you build a culture of accountability without invading privacy by allowing you to monitor activity to see how people are doing while blurring apps and screenshots to avoid capturing personal details. This gives you a snapshot of your company’s health.

Our payroll options also bring in the wage data you need to understand the dynamics of productivity vs wages in your organization.

From our perspective, there are a few safeguards that employers can take: Pay people well, offer benefits and health-focused incentives, and create reward programs highlighting your stars.

Are you ready to elevate your remote team’s efficiency? Experience seamless collaboration, enhanced productivity, and transparent work processes with Hubstaff – the leading remote employee monitoring software!

Most popular

The Fundamentals of Employee Goal Setting

Employee goal setting is crucial for reaching broader business goals, but a lot of us struggle to know where to start. American...

Data-Driven Productivity with Hubstaff Insights: Webinar Recap

In our recent webinar, the product team provided a deep overview of the Hubstaff Insights add-on, a powerful productivity measurem...

The Critical Role of Employee Monitoring and Workplace Security

Why do we need employee monitoring and workplace security? Companies had to adapt fast when the world shifted to remote work...

15 Ways to Use AI in the Workforce

Whether through AI-powered project management, strategic planning, or simply automating simple admin work, we’ve seen a dramatic...